One such example, but in the opposite direction (i.e., where an American invests abroad) is the Controlled Foreign Corporation ("CFC") rules. These rules are found starting in IRC Section 951 through 965 and are commonly referred to as "Subpart F" (because they are part of Subtitle A, Chapter 1, Subchapter N, Part III, Subpart F of the IRC).

The CFC rules were created to target situations where a U.S. person uses a foreign entity which it owns (this is the CFC) to earn specific types of income and taxes that income in the year it was earned by the foreign entity. But for the application of Subpart F, this income would not be currently subject to tax and would only be taxed in the U.S. when it was paid as a dividend from the CFC to the U.S. owner. Congress therefore targeted two situations which it felt to be abusive. First, it targeted certain situations where the income didn't really need to be earned by that entity and it should therefore be assumed that the U.S. owner is conducting the business through the CFC for the purpose of avoiding U.S. tax through potentially endless deferral. Second, it targets certain types of transaction by CFCs which have the practical effect of circumventing the need for the CFC to pay a dividend.

Volumes can be written about Subpart F. For this post, I will begin to describe the first category above and I will hopefully get to the second category (IRC Section 956 dividends in case you want to skip ahead) in a later post.

IRC Section 951 says that all "U.S. shareholders" of a "controlled foreign corporation" who earn "subpart F income" are required to include such income in their net income in the year in which it is earned. This means essentially that certain types of income - "subpart F income" - are deemed to be earned both by the CFC and the US Parent simultaneously. But in order to know when this rule will apply, each of the preceding phrases needs to be defined in order to understand how this works.

- CFCs are defined in IRC Section 957 as any foreign corporations who are owned at least 50% by U.S. persons determined by reference to either voting power or the total value of the company ("vote or value")

- "U.S. shareholder" is defined in IRC Section 951(b) as any U.S. person who owns 10% or more by vote or value of a CFC

- "Subpart F Income" is the most involved definition and includes several different categories of income, each of which is a term of art under the Code and needs to be defined through additional complex rules in turn.

Subpart F Income Categories

Since each of the various categories has lots of nuanced rules that I have no intention of adequately explaining here, I will merely discuss the underlying themes of these categories so you as the new practitioner can approach the rules with a framework in mind.

One category of subpart F income, called Foreign Base Company Income, is from my experience the most important category for most international businesses. Within that category, there are several subcategories, each of which can be understood based on the U.S. tax policy underlying the definition. One of these, Foreign Personal Holding Company Income, essentially aims to target CFCs who earn certain types of passive income and make that income taxable in the U.S. The idea behind this, similar to Passive Foreign Investment Company (PFIC) rules, is to make it difficult for U.S. taxpayers to defer income recognition through the use of foreign investment entities.

The next set of Foreign Base Company Income types you should watch out for are two categories covering one basic problem: Foreign Base Company Sales Income and Foreign Base Company Services Income. These categories target business arrangements where a CFC is doing business in a foreign country other than its resident country, either earning sales or services income. The idea here is that allowing a CFC to earn income all around the world will make it very easy for U.S. persons to set up shell companies to unfairly defer income from their worldwide operations without necessarily paying local taxes in the jurisdiction where they earn the income. The rule here concedes some deferral if you are willing to set up a corporation in the country where you want to make your money (which means you will likely be taxed locally) but draws the line on this deferral where it is likely to cut down on abusive structures.

The last type of Foreign Base Company Income is Foreign Base Company Oil Income. I'm going to ignore that category since it applies to a narrow range of businesses.

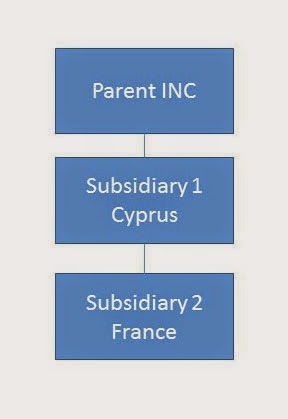

An Example - US Company with two Subsidiaries

An example of a relatively common situation in a multi-national company involves a situation where a CFC makes a loan to another CFC in a different country. In additional, one of the CFCs has branches in other countries and has sales in those countries.

In this example, Subsidiary 1, located in Cyprus, wants to loan money to Subsidiary 2, located in France. Absent any issues arising under the Code, this can be very beneficial for several reasons. First, it is better to loan the money from Cyprus than from the U.S. Parent because the interest income generated from the loan will be taxed at a lower rate in Cyprus than in the U.S. (about 12.5%). Second, France will generate interest expense on the loan which will erode the tax base in France (where there is a similarly high corporate tax rate compared to the U.S.) and shift the income to Cyprus, which has a significantly lower rate. All in all, this would be a pretty great outcome and would result in significant tax savings, just for doing nothing but cleverly moving some money around. (I am ignoring several potential issues with this which may affect the outcome)

However, the CFC rules prevent this from working because the interest income will be considered Foreign Personal Holding Company Income. This interest income will be immediately recognized by both Subsidiary 1 (obviously) and also by Parent INC under the Subpart F income rules. As a result, the Parent will recognize income in the amount of the interest payments and such income will be subject to corporate rates of 35%. This defeats the benefit we observed above and is just one of many deterrents to erosion of the U.S. tax base through foreign related entities.

There used to be a rule which expired at the end of 2013 which would have helped us. The rule, known in the biz as the "look-through" rule exempted passive income which originated from sources which earned non-Subpart F income. Under this former rule, if Subsidiary 2 had been making money in a non-Subpart F way (such as through sales within its country of residence), it could then borrow money from Cyprus and make interest payments to it without triggering Subpart F. So this rule was pretty helpful for taxpayers, but it was part of the "tax extender" legislation and it expired along with most of the rest of the tax extenders. Many practitioners expect it to return when Congress eventually gets around to doing a new tax extenders bill but this should only be treated as speculation until such legislation is actually passed.

No comments:

Post a Comment